Kristin Bouldin (left), Noell Wilson (center), Jeff Washburn (right)

Kristin Bouldin (left), Noell Wilson (center), Jeff Washburn (right)

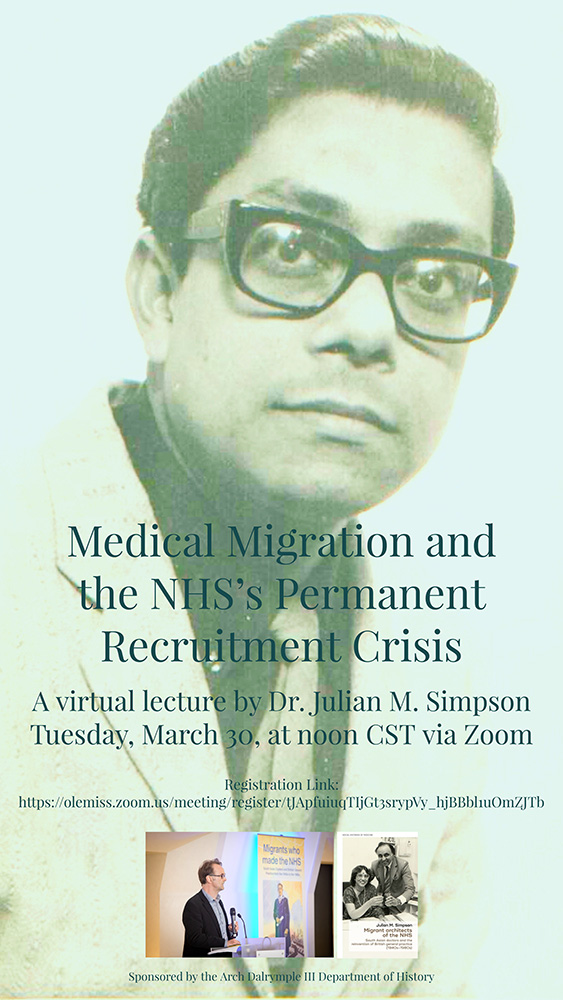

Lecture Title: Medical Migration and the NHS’s Permanent Recruitment Crisis

Speaker: Julian M. Simpson

When: Tuesday, March 30, at noon CST via Zoom.

Registration: To register for the virtual lecture, simply click on the following link: https://olemiss.zoom.us/meeting/register/tJApfuiuqTIjGt3srypVy_hjBBbl1uOmZJTb

Lecture Abstract: Using oral history interviews and archival research I will explore the complex nature of the relationship between the UK’s National Health Service and the medical migrants who have played an essential role in staffing it since its inception in 1948. While lip service has been paid to their numerical importance, there has been less focus on the specific nature of the roles they have performed in the British healthcare system and what this reveals about the culture of medicine and the structure of the NHS. Medical migrants need to be understood as providing ‘special’ labour rather than simply ‘additional’ labour. In the first four decades of the NHS, migrant doctors were disproportionately represented in the provision of care for the least affluent and most vulnerable sections of society. I would argue that this is the core function of the NHS, hence that they were its architects. Their presence in fields such as psychiatry or areas of medicine such as inner-city general practice was not simply the product of a shortage of doctors in absolute terms. It was about the low-status of these forms of work within the British medical profession, and the emigration of their UK colleagues who chose to shun the opportunities that migrants used to build careers. Similar patterns in the deployment of medics can be observed in other westernised medical systems and I will conclude by highlighting the different ways in which this history is relevant to our understanding of global public health.

Speaker biography: Julian M. Simpson is an independent writer, researcher, and translator. He has worked in a number of capacities for various organisations, including the BBC World Service, the Scottish Refugee Council, the l’Afrique à Newcastle Festival and the University of Manchester. He is the author of Migrant architects of the NHS: South Asian doctors and the reinvention of British general practice (1940s-1980s) (Manchester University Press, 2018) and co-editor of History, Historians and the Immigration Debate: Going Back to Where We Came From (Palgrave, 2019).

The history of red-lining is one increasingly well-known within and beyond the academy. In the 1930s, as part of an attempt to shore up the struggling economy by underwriting home mortgages, the government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), developed a series of guidelines and criteria for assessing the risk of lending in urban areas. HOLC criteria drew heavily on the racial logics employed by lenders, developers, and real estate appraisers. Thus, “A-rated” neighborhoods, those associated with the least risk for banks and mortgage lenders, tended to be exclusively white. While, “D”-rated areas, deemed the most-risky, included large numbers of black and/or other non-white residents. These neighborhoods were color-coded red on HOLC maps, hence the term red-lining. They were often denied home loans.

The history of red-lining is one increasingly well-known within and beyond the academy. In the 1930s, as part of an attempt to shore up the struggling economy by underwriting home mortgages, the government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), developed a series of guidelines and criteria for assessing the risk of lending in urban areas. HOLC criteria drew heavily on the racial logics employed by lenders, developers, and real estate appraisers. Thus, “A-rated” neighborhoods, those associated with the least risk for banks and mortgage lenders, tended to be exclusively white. While, “D”-rated areas, deemed the most-risky, included large numbers of black and/or other non-white residents. These neighborhoods were color-coded red on HOLC maps, hence the term red-lining. They were often denied home loans.

HOLC and redlining had a dramatic effect on American cities with consequences lasting to the present day. Yet, the image of the HOLC’s color-coded maps suggests a more static relationship between lending and urban America than actually existed. In today’s episode, Rebecca Marchiel tells a more complex and nuanced story of white and black community activists who engaged with the federal government and banks in an effort to expose redlining—in its multiple forms—and imprint their own “financial common sense” on banking. In doing so, she undercuts notions that the reality depicted in HOLC’s maps was set in stone by the 1960s, when residents in Chicago’s West Side first became suspicious that they had become victims of red-lining, while at the same time revealing the alternative models of financing proposed by community activists in the urban reinvestment movement.

Take a listen: Rebecca Marchiel’s Podcast Episode

On February 6, 2021, Ph.D Student Austin Nicholson, published the piece below in the “Made by History” section of the Washington Post.

“History reveals the danger of Republicans indulging Marjorie Taylor Greene”

By Austin Nicholson

February 6, 2021

The remarks came in response to the House voting to strip Greene of her committee assignments. But while this was an unprecedented act of discipline against a member, only 11 Republicans supported it. By contrast, 199 of them voted against the move, with many ignoring Greene’s rhetoric and focusing instead on the dangers of the precedent being set by the majority party dictating the committee assignments of a member of the minority party. This reveals that Greene is far from a pariah and that procedural concerns trouble her peers more than her rhetoric. Some of her fellow Republicans supported her candidacy, and she won Georgia’s 14th Congressional District with 75 percent of the vote.

While commentators have painted Greene’s radicalism as shocking and unprecedented in the hallowed halls of Congress, history provides at least one clear antecedent for Greene — and a warning to her Republican colleagues on the dangers of excusing her rhetoric or treating it lightly.

A century ago in 1920, another unabashed conspiracist was elected to the House from the Deep South — John E. Rankin of Mississippi’s 1st Congressional District. Taking office at the apex of Jim Crow disfranchisement, Rankin was far from the only dedicated White supremacist in Congress. But his outspoken extremism on a range of issues was unmatched. Casting himself as a “real, red-blooded American” and a lonely defender of “American institutions,” Rankin combined his hatred for Black Americans, Japanese Americans and Jews into an explosive cocktail of bigotry. His worldview was defined by vast international conspiracies and suspicion of pervasive internal subversion, and he often connected his various targets to the perceived threats of socialism or communism.

During the 1930s, Rankin focused on keeping the United States out of foreign wars and alliances, including opposing efforts to aid Britain in its fight against Nazi Germany. On the floor of the House, Rankin blasted efforts to drag the United States into World War II as the work of an international communist cadre that included munitions makers, Wall Street executives, East Coast journalists and Hollywood elites, all “in collusion with Moscow to overthrow the American republic.” He blamed the same group for racial intermarriage, integration efforts and immigration, tying them all to a grand scheme that threatened to “destroy the last vestige of our Christian civilization.”

Yet Rankin’s impact went beyond his rhetoric. Throughout Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, Democrats relied on the Southern segregationist wing of their party in Congress to codify key elements of the New Deal. Since the South was one-party territory, the segregationists accrued seniority, which let them chair committees and subcommittees. To protect Roosevelt’s agenda and the party’s majority, therefore, Democrats accommodated outspoken racists such as Rankin and his fellow Mississippian, Sen. Theodore Bilbo.

Due to mass disfranchisement, Rankin was elected to 16 terms by the votes of a small number of White elites in northeast Mississippi, and he slowly gained the powers that came with seniority in the House. Emboldened by the implicit support of his colleagues, Rankin’s racist and anti-Semitic views shaped federal policies and destroyed lives.

For example, after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II, Rankin jumped to frame the conflict in racial terms. On the House floor, he declared a “race war” between White civilization and “Japanese barbarism.” Citing President Andrew Jackson’s policy of Indian removal, he called for the imprisonment and deportation of all Americans of Japanese ancestry, based solely on their ethnic heritage and regardless of their citizenship status.

The very next day, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which laid the foundation for the policy of Japanese internment. While it did not go as far as Rankin wanted, the policy had echoes of his bigotry. Rankin continued his efforts to strip Americans of their constitutional rights, arguing against birthright citizenship for Japanese Americans, demanding harsher treatment of those interned on the West Coast and opposing Hawaiian statehood solely based on the islands’ substantial Japanese population.

Rankin was also deeply anti-Semitic. He often fixated on Jews, equating them with Communists, no matter their loyalties. In 1941, Rankin denounced a meeting of “international Jews” in New York’s financial district. Infuriated, his Jewish colleague, Rep. M. Michael Edelstein (D-N.Y.), delivered an impassioned rebuttal, left the House floor, collapsed and died of a heart attack in the House lobby. Rankin was unnerved, and the outrage of his colleagues caused him to lay low for a time, but he never apologized for the speech that had angered Edelstein to death.

Rankin continued gaining power in Congress, despite railing against the Red Cross for refusing to segregate the blood of White, Black and Japanese donors, shouting racial slurs on the House floor, privately entertaining Nazi sympathies and refusing to sit next to a Black colleague from his own party. In 1945, he ensured the establishment of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which paved the way for McCarthyism the following decade. Most notably, his powerful position on the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee, which he later chaired, allowed him to influence the language of the G.I. Bill to guarantee the denial of education and housing benefits to Black veterans across the South — a policy that helped ensure the rise of the racial wealth gap and vast economic inequality that lingers to today.

Rankin’s 32-year career ended only when Mississippi lost a seat in reapportionment, forcing his retirement at age 70. In 1952, his district was consolidated with another, pitting Rankin against fellow Rep. Thomas Abernethy in a tough primary race. Abernethy, who campaigned on his relative youth and his ability to aid Mississippi farmers through his position on the House Agriculture Committee, narrowly prevailed. But even then, the outcome was far from a repudiation of Rankin or his ideas.

Like Rankin, Greene has promoted false conspiracy theories about powerful elites with a master plan to destroy Western civilization — rhetoric that is arguably even more dangerous in the age of social media, when millions can access her words with a click. And like Rankin, Greene represents one of the most partisan districts in the nation and is unlikely to lose reelection to any member of the opposing party.

This is why what House Republicans decide to do about Greene’s controversial remarks matters. Will they accommodate their colleague or take sustained and decisive action to limit her influence? If Thursday’s vote was any indication, they seem more apt to follow a path that history shows to be dangerous. The case of Rankin reveals that failing to marginalize Greene could have serious policy ramifications, affecting millions of Americans’ lives and well-being.

Ashleen Williams recognized for showing exemplary promise as higher education leader

Ashleen Williams (center), a doctoral student in history at the University of Mississippi, welcomes a group of first-generation transfer students to campus. Williams, who teaches in the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College, has been honored as a future leader in higher education. Photo by Logan Kirkland/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

January 19, 2021 by

A doctoral student in history at the University of Mississippi has been awarded a prestigious honor for future leaders in higher education.

Ashleen Williams, who also teaches in the university’s Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College, is among nine recipients of the Association of American Colleges and Universities‘ annual K. Patricia Cross Future Leaders Award. The award recognizes graduate students who show exemplary promise as future leaders of higher education and who are committed to academic innovation in the areas of equity, community engagement, and teaching and learning.

The awards honor the work of K. Patricia Cross, professor emerita of higher education at the University of California at Berkeley.

“This award is particularly meaningful because of who the award is named for and the example K. Patricia Cross set for young educators for excellence in teaching and learning,” Williams said. “This award is also a chance to connect with other graduate students and scholars across the nation who are committed to questions of equity and community engagement, and I’ve felt very inspired by learning from the work they are doing.”

Among other activities, Williams’ award recognizes her involvement in the Honors College First-Gen Student Network, which helps first-generation students navigate the college experience. She created a lecture series given by successful first-generation Mitchell, Truman and Fulbright scholars.

Williams came to the Honors College from Montana, following excursions to Northern Ireland and the Middle East. As a 2013 Mitchell Scholar, Williams travelled to the University of Ulster to earn her master’s degree in applied peace and conflict studies.

Her dissertation focused on “Writing on the Walls: Examination of the Contestation of Space in Bahrain through Graffiti and Social Media,” a study she began while holding a Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship in Bahrain.

The 2021 Cross recipients were chosen from a pool of 200 nominees from 121 institutions who have demonstrated the potential for leadership in teaching, academic innovation and community engagement. The award is open to all doctoral-level graduate students who are planning careers in higher education, regardless of academic department, and have been nominated by a faculty member or administrator.

Graduate students in fields where a master’s degree is the terminal degree are also eligible.

The 2021 winners will be recognized at AAC&U’s virtual annual meeting, “Revolutionizing Higher Education after COVID-19,” set for Jan. 20-23. They will be honored and introduced to the AAC&U community during the opening plenary session.

The recipients also will participate in the K. Patricia Cross Future Leaders Session, which will be moderated by José Antonio Bowen.

“I plan to use that opportunity to learn more from the other recipients, to attend sessions that will help transform my thinking, and participate in conversations about innovation and equity in education,” Williams said.

Williams’ recognition is well-deserved, said Douglass Sullivan-González, dean of the Honors College.

“As our senior Barksdale fellow, she leads by example how to engage our large academic community with the key questions of the day,” he said. “Ashleen has poured herself into working with first-generation students and has been recognized for these accomplishments both in our college and by the university administration.

“She simply practices what she preaches, and we are honored that she has garnered a coveted spot with the K. Patricia Cross Future Leaders Award foundation.”

As an undergraduate at the University of Montana, Williams was president of the Associated Students and a student/student mentor in the Davidson Honors College. She completed a bachelor’s degree in political science and history, and also studied Arabic as a Georgetown-Qatar Fellow at Qatar University and at the Yemen College for Middle East Studies in Sana’a.

For more information about AAC&U, its annual meeting or the K. Patricia Cross Future Leaders Award, visit http://www.aacu.org.

Historian Carol Anderson is set to discuss the history of voter suppression and how it relates to the right to vote in 2020 for the annual UM Gilder-Jordan Lecture in Southern Cultural History at 6 p.m. Oct. 13. Because of ongoing health concerns, this year’s lecture will be conducted virtually.

OCTOBER 7, 2020 BY REBECCA LAUCK CLEARY

With the presidential election only weeks away, voting and how to do so are on the minds of many Americans. A historian who studies public policy with regards to race, justice and equality will visit the University of Mississippi for a discussion of the history of voter suppression and how it relates to the right to vote in 2020.

With the presidential election only weeks away, voting and how to do so are on the minds of many Americans. A historian who studies public policy with regards to race, justice and equality will visit the University of Mississippi for a discussion of the history of voter suppression and how it relates to the right to vote in 2020.

Carol Anderson, the Charles Howard Candler Professor of African American Studies at Emory University, will give the annual Gilder-Jordan Lecture in Southern Cultural History at 6 p.m. Oct. 13. The event will be held virtually this year because of COVID-19 and is open to the public once they register at https://bit.ly/2Evgyhy.

Her talk, “One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy,” is also the title of her recent book, which was long-listed for the National Book Award in Non-Fiction and was a finalist for the PEN/Galbraith Book Award in Non-Fiction.

Katie McKee, director of the UM Center for the Study of Southern Culture, said she is delighted to welcome Anderson to discuss issues deeply relevant at the moment: voting rights and race in America.

“The Gilder-Jordan lecture gives us, year after year, the opportunity to invite the nation’s leading historians to our stage, and this year is no exception,” McKee said. “We’re excited to be hosting these timely discussions.”

Also on Oct. 13, Anderson will lead a “Black in the Academy” virtual discussion at 4 p.m. for graduate students, facilitated by Shennette Garrett-Scott, UM associate professor of history and African American studies. Anderson’s contributions to the ongoing Twitter conversation “Black in the Ivory,” created by Sharde Davis, amplify the voices of “Blackademics” to speak truth about racism in academia.

Finally, at 6 p.m. Oct. 14, Anderson will participate in a virtual roundtable discussion about voter suppression with Jim Downs and Kevin M. Kruse. The conversation is sponsored by the Center for the Study of Southern Culture and the University of Georgia Press as part of the Voting Rights and Community Activism series.

Downs is coeditor of the UGA Press History in the Headlines series and editor of the recent “Voter Suppression in U.S. Elections,” and Kruse studies the political, social and urban/suburban history of 20th-century America.

Ethel Young Scurlock, associate professor of English and African American studies and senior faculty fellow of the Luckyday Residential College, said the lecture will be momentous and Anderson’s words will help people find new ways to examine the role of policy in their own communities.

“Her scholarship digs deep into issues of how policy can impact the everyday lives of U.S. citizens, with special attention to how policy and practices can impact African American communities,” said Scurlock, who is also director of the UM African American studies department.

“Her rigorous research is important because it reminds us that disrupting the impact of racism is not about trying to change hearts of people; it is about changing policies that impact how people are able to exist in their communities.”

Anderson’s research has garnered substantial fellowships and grants from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Ford Foundation, National Humanities Center, Harvard University’s Charles Warren Center, the Committee on Institutional Cooperation (The Big Ten and the University of Chicago) and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Noelle Wilson, the UM Croft Associate Professor of History and International Studies, said she looks forward to Anderson’s lecture.

“The history department is thrilled to have Professor Anderson join us in this 2020 election season when remembering hard-won lessons of the past is particularly critical for making certain as broad an electorate as possible participates in our November presidential decision,” said Wilson, also chair of the history department.

“The Gilder-Jordan Lecture is one of the most anticipated events of our fall semester, and we look forward to encouraging students, faculty and the community at large to engage with Anderson’s work through this event.”

Anderson is the author of “Eyes Off the Prize: The United Nations and the African-American Struggle for Human Rights, 1944-1955,” which was published by Cambridge University Press and awarded both the Gustavus Myers and Myrna Bernath Book Awards. In her second monograph, “Bourgeois Radicals: The NAACP and the Struggle for Colonial Liberation, 1941-1960,” also published by Cambridge, Anderson uncovered the long-hidden and important role of the nation’s most powerful civil rights organization in the fight for the liberation of peoples of color in Africa and Asia.

Her third book, “White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of our Racial Divide,” won the 2016 National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. A New York Times bestseller and New York Times Editor’s Pick, it is listed on the Zora List of 100 Best Books by Black Woman Authors since 1850. Her young adult adaptation of “White Rage, We are Not Yet Equal” was nominated for an NAACP Image Award.

Anderson is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Miami University, where she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in political science, international relations and history. She earned her doctorate in history from Ohio State University.

Organized through the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, the African American studies program, Center for Civil War Research and the Arch Dalrymple III Department of History, the Gilder-Jordan Speaker Series is made possible through the generosity of the Gilder Foundation. The series honors the late Richard Gilder, of New York, and his family, as well as his friends, Dan and Lou Jordan, of Virginia.

Registration information is available at https://southernstudies.olemiss.edu/ or by emailing Afton Thomas at amthoma4@olemiss.edu.

OCTOBER 2, 2020 BY KELLIE SMITH

Don Guillory, a UM doctoral student in history, presents his research on slavery and enslaved people in Oxford during the 2020 TEDxUniversityofMississippi presentation in February.

“When people don’t have a narrative, they don’t have value in the eyes of the greater society,” said Don Guillory, a doctoral student in the University of Mississippi‘s Arch Dalrymple III Department of History.OXFORD, Miss. – What happens when the life stories of a group are destroyed or distorted?

Guillory has given a voice to the many enslaved people who lived in and around Oxford before the Civil War by illuminating their history in tours of the UM campus, where some of the iconic structures – such as the Lyceum, which houses the chancellor’s office – were built by slave labor.

The tours are an initiative of the UM Slavery Research Group. Created in 2013, the group is composed of faculty and staff working across disciplines to learn more about the history of slavery and enslaved people in Oxford and on the Ole Miss campus.

This fall, Guillory will give the tours via video, a change that he feels will have both positive and negative impacts on the experience.

Because the actual trekking will be eliminated, the video version of the tours will expand their footprint to sites farther from campus. These include Rowan Oak, which was built before the Civil War and purchased by William Faulkner in 1930 as his Oxford home, and was constructed with slave labor.

The tours are an initiative of the UM Slavery Research Group. Created in 2013, the group is composed of faculty and staff working across disciplines to learn more about the history of slavery and enslaved people in Oxford and on the Ole Miss campus.

This fall, Guillory will give the tours via video, a change that he feels will have both positive and negative impacts on the experience. Because the actual trekking will be eliminated, the video version of the tours will expand their footprint to sites farther from campus. These include Rowan Oak, which was built before the Civil War and purchased by William Faulkner in 1930 as his Oxford home, and was constructed with slave labor.

The revamped tours also include Hilgard Cut, a railroad cut constructed by enslaved people in 1858 to bring students to Oxford from other parts of the South; and Burns-Belfry Church, founded in 1910 as the first African American church in Oxford.

“The video tours will have more content but less contact,” Guillory said. “They’ll cover more territory but without face-to-face interaction.”

A primary goal of the tour is to let artifacts and creations of enslaved people create a narrative for their lives that reflects their reality and voice. The narratives can be “challenging” because they present an alternative reality to the stories that slave-owning families created about the people they held in bondage and their relationships with them, Guillory said.

For years, slave owners spread a false narrative that often served as an “official” history of slavery, one that was accepted not only regionally, but nationally.

Guillory underscored his point in a TEDxUniversityofMississippi presentation in February 2020. He compared lost narratives to “missing threads in the fabric of humanity,” a fabric he hopes to reweave.

“The history department is thrilled to support graduate students engaging in public history projects like this tour because they connect a broad audience of not only university community members, but also Oxford residents, such as high school students, to the work of professional historians,” said Noell Wilson, associate professor and chair of the department.

“We are grateful for Don’s ingenuity and technical savvy in moving the tours online during the pandemic and are optimistic that the tours will now reach an even larger audience through this virtual platform.”